by Vrinda Nair and Swaraj Choudhary

Antonio Gramsci and the Concept of Cultural Hegemony

Antonio Gramsci was an Italian Marxist thinker, writer and political leader. A vocal critic of fascism writing during the the reign of the dictator Benito Mussolini, he did most of his major work after being imprisoned for his involvement with the Italian Communist Party, of which he was a founding member. His Prison Notebooks, a series of essays, reshaped Marxist theory by emphasizing the power of culture and ideology in maintaining state control.

Gramsci’s insights stemmed from a fundamental question: If the material conditions for revolution exist, why isn’t revolution happening? He argued that it wasn’t enough to focus on the economy or wait for class struggle to naturally erupt. The answer was in understanding the deeper mechanisms through which the state secures consent, which is through culture and ideology.

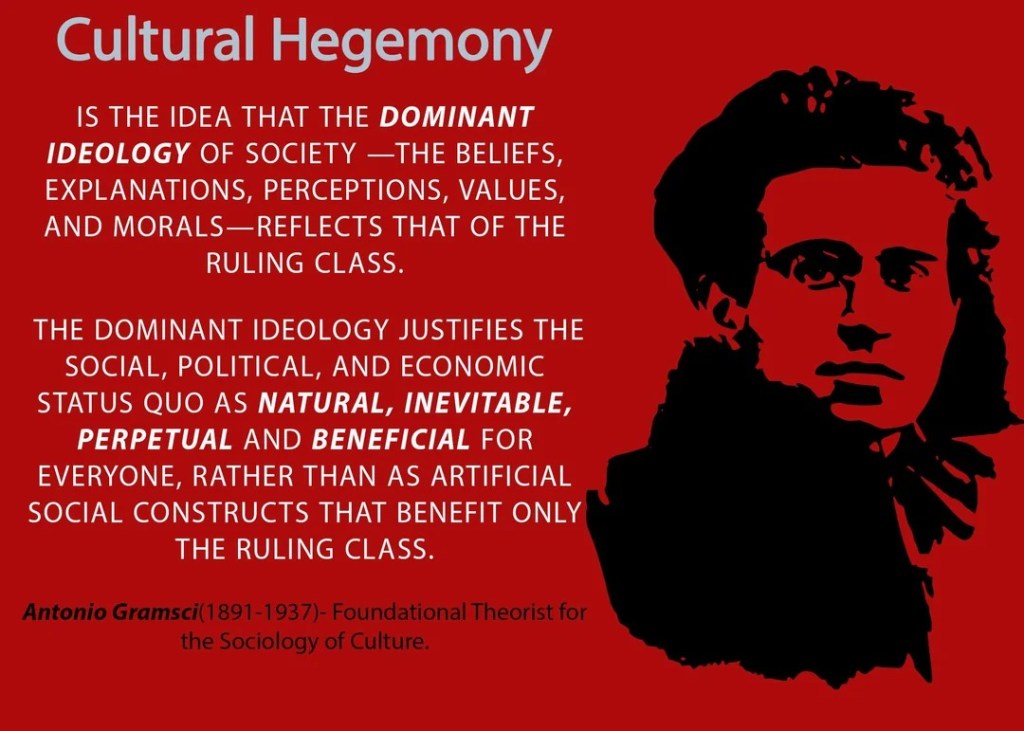

Gramsci introduced the concept of cultural hegemony, which refers to the domination of a society by the ruling class, who manipulate the culture so that their worldview becomes the accepted cultural norm. People begin to see their social and material conditions as natural and inevitable. “Things are the way they are because they have always been this way.” This deterministic worldview discourages individuals from demanding change and encourages them to accept their material conditions as natural and unchangeable simply because things have always been that way. The ideology of the state becomes deeply embedded in everyday life, so much so that it becomes invisible.

This silent dissemination of ideology means that people internalize values, beliefs, and norms that serve the ruling class, often without realizing it. According to Karl Marx, those who control the means of production also control mental production. Thus, the ideas of the ruling class are projected as the ideas of the whole society, often in the guise of serving public welfare. Their worldview misrepresents the social, political and economic status quo as natural, inevitable and perpetual conditions that benefit all classes, rather than as artificial social constructs benefiting only them.

Institutions like the police, military, schools, prisons, and religious organizations are all involved in reproducing the dominant ideology. These institutions appear to serve society, but in reality, they protect the interests of the elite. For instance, the police as an institution exists not for public safety but they exist to protect the ruling class from the working class, from those who are perceived as threats to the establishment.

Women’s oppression is a case in point: patriarchal control over women’s bodies and sexuality is framed as honour and morality. Women are made to feel shame in the event of rape or a sexual assault. They are treated as secondary citizens, their value tied to men’s existence. This, too, is an ideological construct shaped by cultural hegemony.

Cultural hegemony explains how dominant ideas are normalized. From childhood, people are encultured through institutions like schools and religious bodies. These systems reinforce class, caste, gender, and religious hierarchies. For example, in India, the idea of Aryan supremacy and caste dominance is perpetuated through distorted histories and rituals. Every day, symbols like gifting dolls to girls and toy guns to boys reinforce gender norms and fixed ideas of femininity and masculinity. Success is defined materially, and even creativity is boxed into elitist definitions that exclude working-class experiences, like that of farmers, from the definition of creativity..

Gramsci noted that even in societies where material conditions are ripe for revolution, people often suffer from false consciousness. False consciousness is where they believe in the legitimacy of the dominant ideology, even when it works against their own interests. This is why, he argued, cultural struggle is just as important as political or economic struggle. He called this the “war of position”- a long, sustained intellectual and cultural struggle wherein a proletariat culture is established to counter the cultural hegemony of the ruling class.

Gramsci believed that everyone is an intellectual, not just the academic elite. However, society recognizes intellect only when it emerges from a particular class. Thus, real intellectual engagement must come from the masses reclaiming their voice and contesting dominant narratives.

This insight is especially relevant when we look at contemporary debates. For example, the ghoonghat system is often presented as a personal choice, but it’s important to ask how are these choices really formed? Why is the purdah or ghoonghat practice in Rajasthan not subjected to the same level of scrutiny or criticism as the hijab often is in India? These contradictions show how selectively cultural practices are politicized, often by reactionary forces. Gramsci warned that when culture becomes political, conservative and dominant groups often take control of the narrative.

The RSS in India exemplifies how cultural organizations can wield significant ideological power. Initially framed as a cultural group, the RSS began with shakhas that offered physical training, but then slowly embedded militaristic and ideological indoctrination. It also distorted history, vilified certain communities, and propagated a narrow, exclusionary idea of nationhood.

In response, Gramsci advocated for progressive forces to enter the cultural domain to wage a war of ideas, to challenge hegemony not just through revolution, but by reshaping beliefs, values, and worldviews. The battle against domination of the ruling class must begin in the realm of culture itself, using art, literature, education, and collective memory to dismantle oppressive ideologies. He asserted that once this “war of position” is won, the revolutionary leaders of the working class will have enough popularity and political power to win the “war of maneuver”, which he defined as an abrupt assault that erupts the established order of the state and civil society

Therefore, Antonio Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony teaches us that the real struggle lies in capturing not just institutions, but minds. Revolution is not only fought in the streets but in classrooms, in books, in rituals, in everyday conversations. And until we engage in this cultural war of position, the structures of domination will remain intact, where they are quietly accepted.