by Nishtha Gupta

Nationalism is one of the most defining forces of the modern world. It shapes identities, mobilises movements and governs how people across vast and diverse regions imagine their belonging to a larger collective. At the heart of nationalism lies the idea of the ‘nation’ — an entity that commands deep loyalty, emotional investment and even sacrifice from its people. But what exactly is a nation, and how does it come into being? These are the questions that political theorist Benedict Anderson addressed in his seminal work Imagined Communities, where he introduced the idea of the nation as an “imagined political community.” His insights reshaped how we understand the origins and persistence of nationalism, especially in post-colonial societies like India.

Anderson argued that nations are not natural entities that have always existed. Rather, they are cultural constructs that emerged under specific historical and technological conditions. He proposed that the nation is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow members, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion. This imagined connection is powerful and enduring, but it is not accidental. It is the product of conscious and unconscious mechanisms that help people across time and space see themselves as part of the same social and political body.

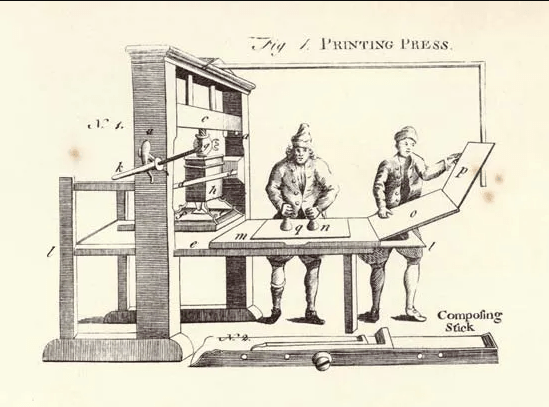

One of the most critical mechanisms behind this imagination, according to Anderson, is print capitalism. This concept explains how the rise of print technology and capitalist enterprise contributed to the creation and spread of national consciousness. The printing press, invented in Europe in the 15th century, revolutionised the production of texts. Before the press, books were laboriously copied by hand, which meant that written texts were expensive, rare and largely confined to religious or scholarly elites. These texts were also often written in Latin or other elite languages, further limiting their accessibility.

With the advent of the printing press, texts could be produced more cheaply and in much greater numbers. Print capitalism refers to the intersection of the printing press and capitalism’s profit-driven motives. The printing press, once introduced, was quickly adapted to mass-produce books, newspapers and pamphlets. This process led to the standardisation of languages, which in turn allowed for greater mutual intelligibility and national unity. People from far-flung areas who would otherwise have no connection to one another began to read the same stories, news and editorials. As Anderson observes, “The convergence of capitalism and print technology on the fatal diversity of human language created the possibility of a new form of imagined community which in its basic morphology set the stage for modern nation.”

Print capitalism, then, was not just about spreading information. It was about shaping a new kind of social consciousness, one that was rooted in shared language, stories and time. Newspapers and novels were particularly instrumental in this process. Anderson famously described the newspaper as “an extreme form of the book,” calling it a “one-day best-seller.” People would read newspapers every morning, knowing that thousands of others were reading the same stories, often at the same time. This ritual created what Anderson called “homogeneous, empty time,” a concept borrowed from Walter Benjamin. It refers to a standardised sense of time in which people, regardless of location, could imagine themselves living parallel lives as part of a unified nation.

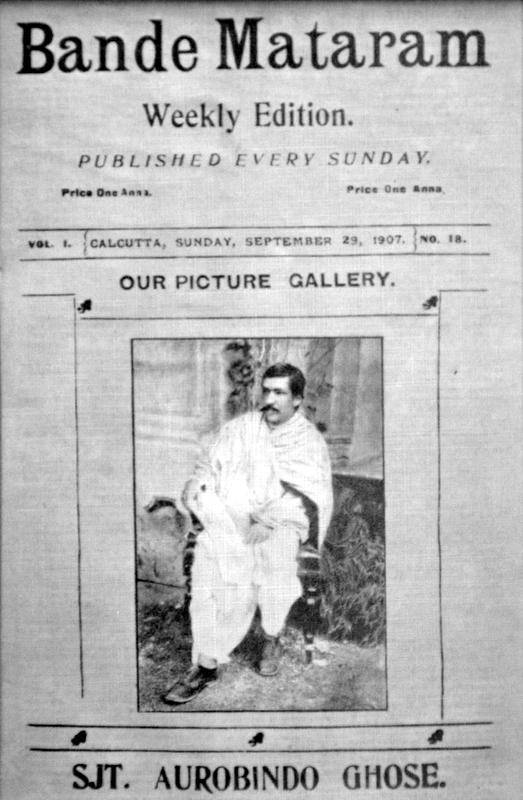

This framework helps us understand how national identity formed even in vast and diverse countries like India. During the colonial period and the freedom struggle, India was marked by linguistic, cultural and regional plurality. Yet, as newspapers began to circulate in various Indian languages and as nationalist literature gained prominence, people began to imagine India as a cohesive nation. Newspapers such as Kesari, Bande Mataram and Young India played a pivotal role in spreading anti-colonial sentiment and unifying readers across the subcontinent. They reported not only on political events but also on cultural practices, social reform and national symbols, helping to weave a shared narrative of resistance and belonging.

Literature too played a key role. Novels like Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay’s Anandamath, which featured the song “Vande Mataram,” created emotional and symbolic anchors for nationalist sentiment. The song later became the national song of India, exemplifying how a literary creation could enter the public imagination and become a rallying cry for political mobilisation. Such works, disseminated through the print medium, allowed people to connect with ideas of nationhood on a personal and emotional level.

Prior to the rise of print capitalism, the idea of a unified national identity was difficult to sustain. Communication was limited, and most people lived and died within localised communities with little awareness of the broader world. Political authority was often exercised through monarchy, religious hierarchy or feudal relations. There was no need, nor any means, for ordinary people to imagine themselves as part of a larger collective beyond their immediate surroundings. In this context, nationalism and the modern nation-state did not exist.

It was only through the spread of mass literacy and the growth of a reading public, both outcomes of print capitalism, that people could begin to imagine national belonging. The printing press made it possible to share ideas across space, while capitalism incentivised publishers to reach new audiences. This dual force helped create what Anderson calls the conditions of possibility for nationalism. In other words, the nation could only be imagined once the material and technological means to disseminate a shared culture were in place.

In contemporary India, the legacies of print capitalism are still visible. The celebration of national holidays like Independence Day and Republic Day, the reverence for the national flag, the symbolic status of the royal Bengal tiger as the national animal and the emotional connection to the national anthem and song are all expressions of a national identity that has been nurtured over time. These are not natural or automatic practices. They are rituals that reinforce the idea of belonging to a nation, sustained and shaped by the media, education and popular culture.

Benedict Anderson’s theory thus invites us to reflect not only on the historical emergence of nations but also on the ways in which they are continuously imagined and re-imagined. Print capitalism was not a one-time event but the foundation of an ongoing process in which shared symbols, narratives and languages enable people to identify with others they will never meet. It reminds us that nationalism is not inevitable but constructed, and that the media we consume plays a powerful role in shaping how we see ourselves and others.

In conclusion, Anderson’s insights into print capitalism and imagined communities offer a profound understanding of how national consciousness is formed. By explaining how technological innovation and capitalist interests created the material basis for shared identity, he shows us that nations are not born, they are made. And in making them, print media did not just inform people about their world, it gave them a world to belong to.

Leave a comment